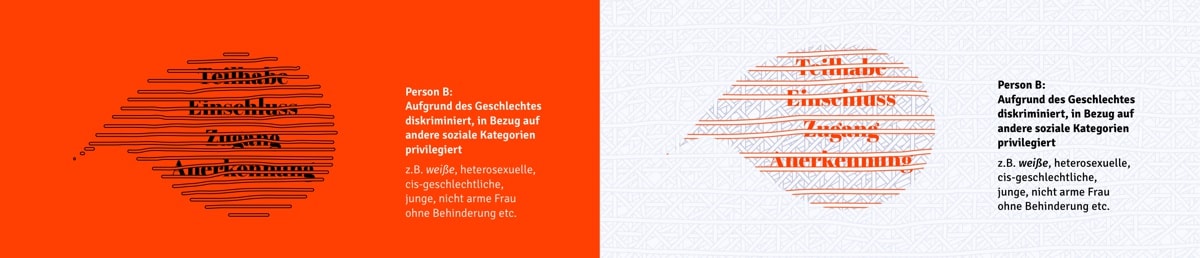

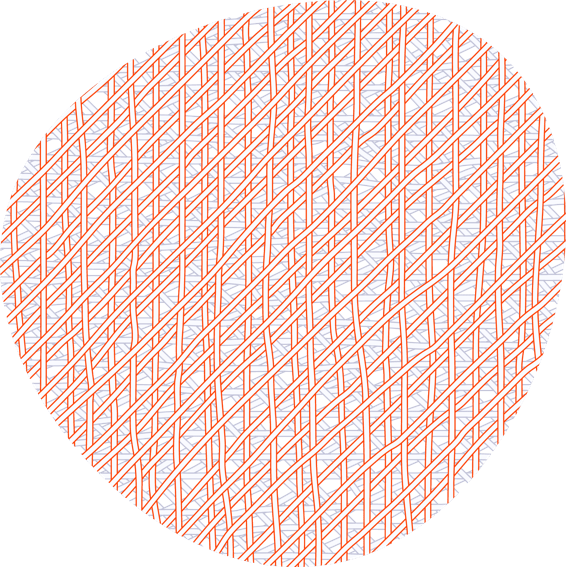

The entire screen is filled with imperfect, »self-drawn« strokes that have an almost white fill and a gray outline. There are many different orientations of strokes (90 degrees, 180 degrees, 45 degrees, etc.). They are interwoven and create a net of strokes. In the foreground the words Access, Inclusion, Participation and Recognition are displayed in large orange letters one below the other.

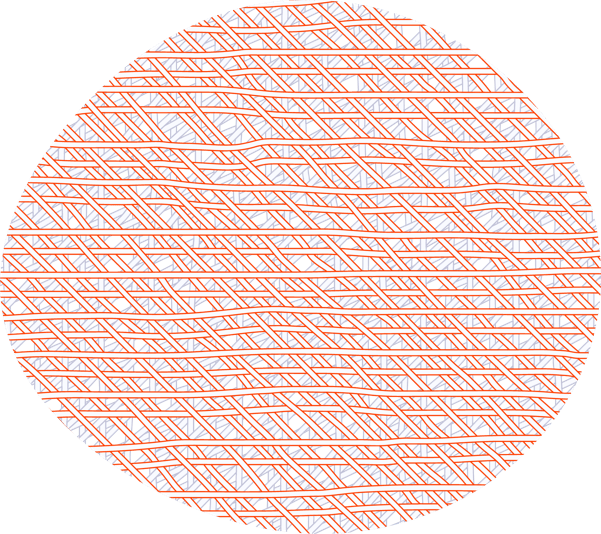

With scrolling, all horizontal strokes are now placed in front of these words and their outlines turn orange. With further scrolling, more and more stroke orientations come to the foreground and their outlines turn orange, so that the words Access, Inclusion, Participation and Recognition become very difficult to read.

Access to resources such as education, the labor market, and housing, social and political participation, social inclusion and recognition. As person A you can read these words without any problems.

What happens when you slip into other people and look at these words from their points of view?

Do you notice anything?

The terms are more difficult to read from this person’s point of view.

Different people face unequal conditions when it comes to access, participation, inclusion and recognition. They are disadvantaged and advantaged differently.

To better understand this, let us take a look at what intersectionality, discrimination, and privilege mean.

In the background is the same net of strokes as in the beginning, but the stroke outlines all have an orange color. The entire screen is filled with this net.

Intersectionality – a first definition

We are all different individuals with different interests, strengths, goals, etc. In addition, several so-called social categories shape us, such as gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race (including ethnicity, nationality, skin color, migration status, language, culture), religion, class (including socio-economic position and background), disability, age, etc. These social categories are dimensions of social power relations: Individuals and groups are differentially disadvantaged, i.e. discriminated against, and advantaged, i.e. privileged, based on these social categories within the framework of prevailing social systems (capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy). This leads to social inequality and asymmetrical distribution of power in our society.

From an intersectional perspective these social categories / power relations do not exist independently and separately of one another. Intersectionality describes the intertwining and interweaving of several social categories / power relations. They interact simultaneously and are in constant interplay with each other.

In the following chapters you will find some explanations and examples.

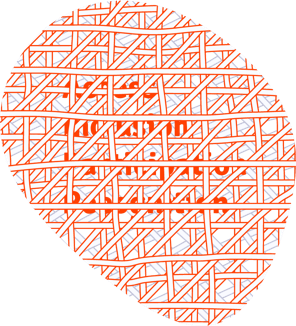

The screen now shows a »zoomed out« version of the net with smaller strokes that have light gray outlines. The entire screen is filled by this net and it remains visible for the next few chapters. On the right, there are three different, organic shapes (organic deformations of circles) arranged one below the other. These shapes emerge from the background net by also being filled with the net and becoming visible by a change in the color of the stroke outlines within the shapes. Within each of the three shapes the words Access, Inclusion, Participation, and Recognition are displayed. Within the first shape, the stroke outlines are gray and all stroke orientations are placed behind the words. Within the shape below, the horizontal strokes are positioned in front of the words and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline and are placed behind the words. Within the bottom shape, all horizontal strokes, vertical strokes, and strokes with a 135 degree orientation occur in front of the words and their outlines are orange, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline and are positioned behind the words.

Discrimination & privilege

Individuals and groups are discriminated against and privileged differently based on social categories. They therefore experience unequal conditions when it comes to access to resources, social and political participation, social inclusion and recognition, etc. Privileges lead to conditions that reproduce advantages and positions of power.

Discrimination and privilege can not be considered separately, because the respective privileged identity within a social category – e.g. white, man, heterosexual, cisgender, or without disabilities – forms the so-called »norm«. And thus the basis for discriminatory structures. Discrimination and privilege can exist together and simultaneously within an individual or a particular social group. Examples of forms of discrimination are racism, sexism, ableism, classism, cis- and heterosexism, anti-Muslim racism, anti-Semitism, anti-Rom*nja racism.

The difficulty lies in the fact that privileges are usually taken for granted and are not visible to those who have them. Privileged people tend not to perceive their privileges as such and consequently do not recognize the barriers and disadvantages that arise for others who do not have these privileges. There is a lack of lived experience that serves as an everyday reminder to deviate from the norm.

A first, important step is to become aware of, reflect on, and acknowledge one’s own privileges. This can start, for example, by learning about the experiences of people who face discrimination.

Case studies from Germany

We now look at case studies of intersectional discrimination in Germany, described for example in reports by the → Center for Intersectional Justice Berlin. Visualizing data from studies supports their illustration. The following examples are a small sample of the many, intersectional forms and experiences of discrimination.

Invitations to job interview

Invitations to job interview

»I called for an internship at the kindergarten and asked for an internship position. After I got an acceptance, I said that I wear a headscarf. Thereupon I got the answer, ›either take off your headscarf or it is not possible‹ (I called a total of 18 kindergartens and got similar answers everywhere).«

Invitations to job interview

Invitations to job interview

»I called for an internship at the kindergarten and asked for an internship position. After I got an acceptance, I said that I wear a headscarf. Thereupon I got the answer, ›either take off your headscarf or it is not possible‹ (I called a total of 18 kindergartens and got similar answers everywhere).«

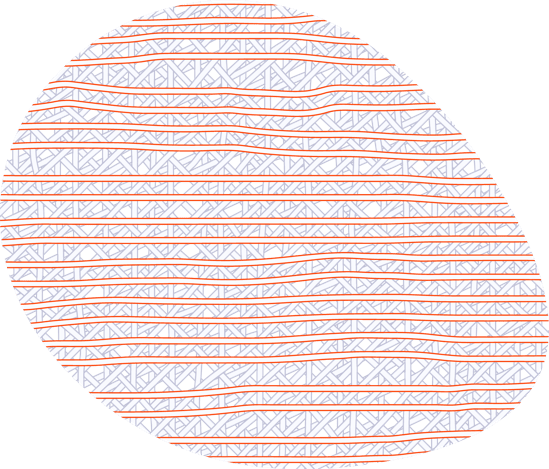

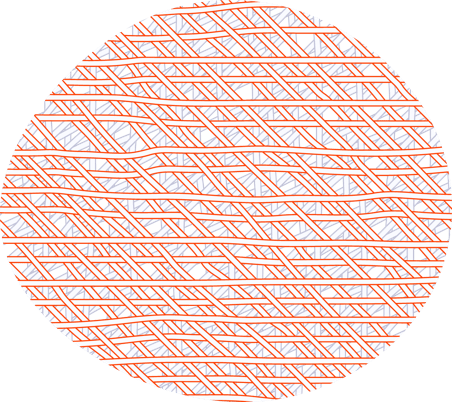

The entire screen is still filled with the net of strokes. The previous shapes disappear and two new organic shapes of different sizes emerge from the net on the right. The size ratio of the two shapes reflects the ratio of 18.8% to 4.2%. The top shape visualizes the 18.8% and its horizontal strokes are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline. The lower shape visualizes the 4.2% and again the horizontal strokes and additionally the two stroke orientations 135 and 335 degrees are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline.

Women with hijab in accessing the German labor market

Women with hijab (Muslim headscarf) experience intersectional discrimination – sexism and anti-Muslim racism – in various areas in Germany. Not only on an individual level, but structurally and institutionally. For example, they experience direct discrimination in accessing the labor market as illustrated by an → experiment by Doris Weichselbaumer from 2016 (p. 12 ff):

1474 applications were sent to companies in Germany, identical in all points except name and application photo. Three different identities were to be tested in this experiment: A woman with a »German sounding« name (Sandra Bauer), a woman with a »Turkish sounding« name (Meryem Öztürk) and a woman with a »Turkish sounding« name (Meryem Öztürk) wearing a hijab in the application photo. All three application photos show the same woman, in one of them she is wearing a hijab.

Sandra Bauer was the most successful candidate: She was invited for a job interview by 18.8% of all companies to which she applied. Meryem Öztürk without a hijab by 13.5%. Meryem Öztürk, who wears a hijab in the application photo, was invited to an interview by only 4.2% of all companies she contacted.

The widely varying number of invitations to the interview shows the intersectional discrimination that women with hijab face when accessing the German labor market.

Despite identical applications, the woman with a hijab and a »Turkish sounding« name would have to send 4.5 times as many applications as a woman with a »German sounding« name and without a hijab to receive the same number of invitations to a job interview.

An example of indirect intersectional discrimination against women with hijab in the German labor market is the so-called »Neutrality Act« in Berlin, which primarily can result in a headscarf ban for Muslim judges, teachers, educators, etc. Such legally legitimized, religious dress restrictions are not directly directed against a particular religious community, but it is reasonable to conclude that the hijab is the implicit target. They are justified with the argument of maintaining the »neutrality« of state institutions.

The bottom shape enlarges (within the shape the horizontal strokes and the two stroke orientations 135 and 335 degrees are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline).

This raises the question of what is considered »neutral« in this context. »Neutrality« is never objective or non-political. »What is considered ›neutral‹ in our case is what appears ›normal‹ from the majority perspective. The headscarf does not appear ›normal‹, therefore it is not read as ›neutral‹. A headscarf ban prevents the headscarf from ever being perceived as normal – and eventually appearing as ›neutral‹.« (Mangold, 2017, translated) Women wearing the hijab are disproportionately affected by these religious dress restrictions, which exclude them, for example, from employment opportunities. Legal legitimization also has the effect of spilling over to other areas – e.g. to employers in the private sector, who are actually outside the scope of such laws – where it becomes accepted and normalized as well.

(Quote from 2017 → report on discrimination in Germany, p. 242, translated)

»People tell me ›you have an intellectual disability‹. I believed that a little bit, once when I was so shocked. But then again ›no, that can’t be‹. I immediately complained, told them ›how can you tell me that? What is this?‹ I can count up to 1000 and more. (...) Nobody thought ›he doesn’t belong here‹. I gave up, they gave up on me too.«

»Gymnasium« attendance

»Gymnasium« attendance

Special education school attendance

Special education school attendance

»Gymnasium« attendance

»Gymnasium« attendance

»People tell me ›you have an intellectual disability‹. I believed that a little bit, once when I was so shocked. But then again ›no, that can’t be‹. I immediately complained, told them ›how can you tell me that? What is this?‹ I can count up to 1000 and more. (...) Nobody thought ›he doesn’t belong here‹. I gave up, they gave up on me too.«

The previous shapes disappear and a new organic shape emerges from the net at the bottom right. Within this, the 90 and 135 degree stroke orientations are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline.

Sinti*zze and Rom*nja children in the German school system

Sinti*zze and Rom*nja have lived in German-speaking countries since the 15th century and are the largest ethnic minority in Europe. They are exposed to prejudices, discrimination, and marginalization, which have their roots in historical events. They were systematically persecuted and murdered in Germany during the Holocaust/Porajmos. Sinti*zze and Rom*nja are still exposed to racist and classist discrimination today – on an individual, structural and institutional level. This is also the case in the German school system. The case of Nenad Mihailovic, shown in the → documentary »Für dumm erklärt - Nenads zweite Chance« from 2018, illustrates this:

In 2017, the 20-year-old successfully sued North Rhine-Westphalia (state of Germany) because he was wrongly classified as intellectually disabled in a placement test when he was 7 years old and as a result had to attend a special education school designed for children with disabilities. At the time of the test, he could only speak Romanes, the language of the Rom*nja. This was equated with low intelligence. Such supposedly »neutral« methods in the educational system, which do not adequately take into account e.g. a lack of language skills, lead to a disproportionate number of e.g. Sinti*zze and Rom*nja children being wrongly diagnosed with special needs and learning disabilities and thus being disadvantaged due to their ethnicity and class.

(Quote by Nenad Mihailovic from the → documentary »Für dumm erklärt - Nenads zweite Chance« from 2018, minute 0–36, translated)

A → study on the educational situation of German Sinti*zze and Rom*nja from 2011 (p. 101 f), edited by Daniel Strauß, highlights this structural discrimination of Sinti*zze and Rom*nja in the education system:

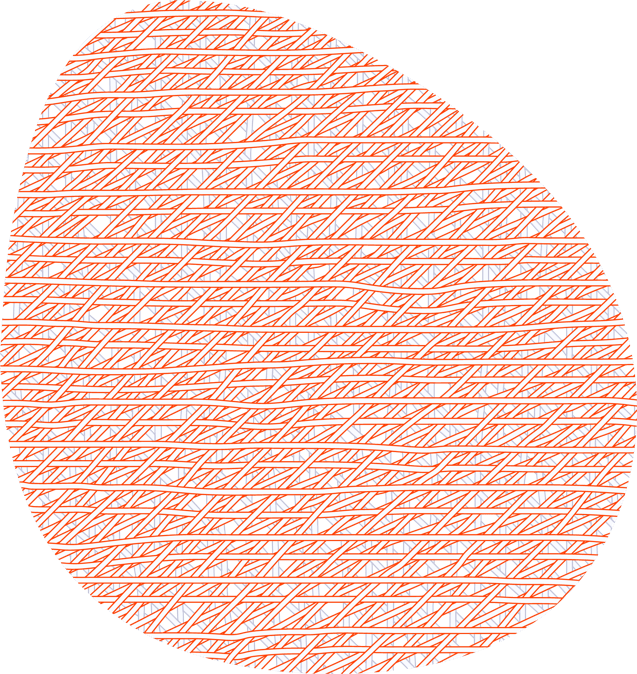

The previously described shape becomes smaller and is now visualizing the 2.3%. The color of the stroke outlines within the shape remains the same (stroke orientations 90 and 135 degrees are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline). At the top right, a second, larger shape emerges from the net. This visualizes the 24.4% and here all stroke orientations have a gray outline. The size ratio of the two shapes reflects the ratio of 24.4% to 2.3%.

Sinti*zze and Rom*nja are disproportionately represented in special education schools designed for children with disabilities and underrepresented at »Gymnasien« (academic secondary schools). Only 6 out of 261 respondents attended a Gymnasium, which corresponds to 2.3%. In the majority population, a total of 24.4% have a university entrance qualification, and in the 20 to 25 year old age group even more than 40%. Only 11.5% of respondents attended »Realschule« (secondary school) (12.3% of the 14 to 25 year olds surveyed). By comparison, in the majority population, over 30% of the 14 to 25 year old age group have a secondary school education.

The lower shape now becomes larger and the upper shape smaller, so that the lower shape is larger than the upper shape. The color of the stroke outlines within the shapes remains the same. The lower shape visualizes the 10.7% and the upper shape visualizes the 4.9%. The size ratio of the two shapes reflects the ratio of 10.7% to 4.9%.

10.7% of the Sinti*zze and Rom*nja interviewed attended a special education school designed for children with disabilities, compared to only 4.9% of all students in the majority population.

The disproportionate representation of Sinti*zze and Rom*nja in German special education schools designed for children with disabilities highlights the intersectional and structural discrimination they face.

The European Court of Human Rights found, for example, in the Czech Republic that the highly disproportionate number of Sinti*zze and Rom*nja children in special education schools designed for children with disabilities in the Czech Republic constitutes indirect discrimination, as supposedly »neutral« placement tests do not take into account certain factors and backgrounds, for example, the lack of language skills. The legally legitimized discrimination of Sinti*zze and Rom*nja children in the school system entails further structural barriers/disadvantages, such as exclusion from the labor market, lack of access to economic resources, difficult access to the housing market, etc.

Experience with sexualized violence

Experience with sexualized violence

Employment

Employment

Experience with sexualized violence

Experience with sexualized violence

Employment

Employment

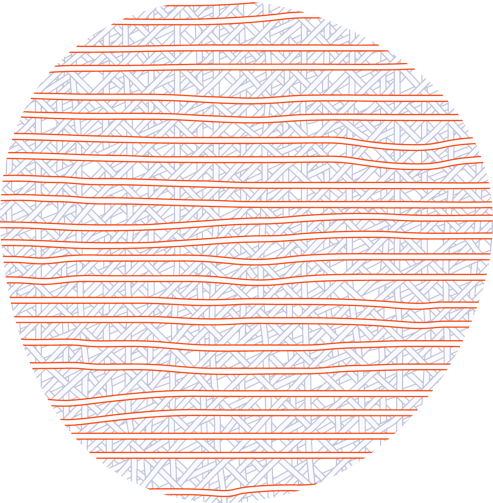

The previous shapes disappear and two new organic shapes of different sizes emerge from the net on the right. The size ratio of the two shapes reflects the ratio of 3 to 1. Within the upper, larger shape, the horizontal strokes and the 45 degree stroke orientation are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline. Within the lower, smaller shape, only the horizontal strokes are in the foreground and have an orange outline, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline.

Women with disabilities: Experience with violence and employment

Women with disabilities experience discrimination on the basis of their gender and disability in various areas in Germany – on individual, structural, and institutional level.

A → study from 2012, published by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (p. 21 & 24), shows the particular vulnerability and endangerment of women with disabilities:

They are at increased risk of becoming victims of physical, sexualized, and/or psychological violence. The 1561 women with disabilities interviewed within the study were two to three times more often exposed to sexualized violence in childhood and adolescence by adults than women in the population average. They are also two to three times more often affected by sexualized violence in adult life.

In the German labor market, women with disabilities experience intersectional discrimination. Prevailing patriarchal structures, such as gender-specific work sectors and the assumption that men provide the main income, combined with prejudices about the skills and competencies of people with disabilities, make it difficult for women with disabilities to access the labor market and thus become independent and self-sufficient. In addition, the lack of accessibility in the work context makes it difficult for all people with disabilities to access the labor market.

The lower shape now becomes larger and the upper shape smaller, so that the lower shape is larger than the upper shape. The color of the stroke outlines within the shapes remains the same. The lower shape visualizes the 74% and the upper shape visualizes the 47%. The size ratio of the two shapes reflects the ratio of 74% to 47%.

A → report by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (p. 170) shows that women with disabilities are more often unemployed than men with disabilities and significantly more often than women without disabilities. In 2013, the employment rate for 18 to 64 year olds in Germany was 47% for women with disabilities, while 52% of men with disabilities and 74% of women without disabilities were employed.

The difference in employment rate shows the intersectional discrimination that women with disabilities experience in the labor market.

The barriers and disadvantages women with disabilities face in the labor market often result in a poor financial situation and/or financial dependence on spouses, partners, other family members, or the state.

Intersectional measures

The examples discussed above show: Special measures are needed to compensate for discrimination and privilege and thus create equal conditions. These must be intersectional and include not only the individual dimension, but above all the structural and institutional dimension of discrimination.

Anti-discrimination measures that, for example, exclusively address sexist discrimination and are thus one-dimensional and not intersectional, tend to target white, heterosexual, cisgender, young, middle-class women without disabilities – the most privileged of the marginalized group. Their lived experiences and interests are foregrounded.

The previous shapes disappear and now, on the left, two new organic shapes emerge from the net. Within each of these two shapes the words Access, Inclusion, Participation, and Recognition are displayed. Within the upper shape only the horizontal strokes are placed in front of these words and their outlines turn orange, all other stroke orientations within this shape have a gray outline and are positioned behind the words. Within the lower shape, all strokes have an orange outline and all are placed in front of the words.

Individuals who experience intersectional marginalization and discrimination are thus not included in one-dimensional measures. For example, the intersectional discrimination against a Black woman cannot be uncovered if only gender or only race is considered, since in a same situation, a Black man and a white woman do not face the same type/form of discrimination. Consequently, such one-dimensional measures cannot overcome intersectional discrimination and marginalization. Individuals and groups may even be further marginalized as a result.

Within the upper shape, the horizontal strokes now move behind the words and their outlines become gray. So within this shape, all stroke outlines are now gray and all strokes are positioned behind the words. In the lower shape nothing changes, all strokes have an orange outline and are placed in front of the words.

Only when the rights, interests, and needs of the structurally most marginalized individuals and groups are taken into account and implemented will all people be liberated from social inequality and asymmetrical power relations. Unequal conditions in access to resources, in social and political participation, in social inclusion and recognition, etc. can be overcome.

The entire background net and the shapes disappear, so that only the words Access, Inclusion, Participation, and Recognition are visible. When scrolling further, these are scaled larger.

And now what?

Intersectionality has hardly been the subject of social discourse, nor has the term found its way into everyday vocabulary in Germany. The political and transformative potential that some authors see in an intersectional perspective is thus still untapped.

»This is to be regretted, because it is desirable that intersectionality as a critical perspective on power relations prevails in general social discourse and is included in a natural way whenever power, inequality, and discursive exclusions are at stake.« (Meyer, 2017, p.155, translated)

Intersectional perspectives focus not only on the individual dimension of discrimination, but equally on institutional, structural, and historical discrimination. This broadens the spectrum of measures that can counter discrimination.

European legal and political frameworks tend to conceptualize discrimination from a one-dimensional perspective. Intersectional perspectives offer the potential to include individuals and groups that remain invisible in traditional, one-dimensional approaches. The Center for Intersectional Justice in Berlin provides some → recommendations to integrate the necessary intersectional perspective into European anti-discrimination work.

And what can I do now?

To make it easier for you to continue tackling the topic, we have listed some initial, possible To Do’s that you can start with right away. This list is by no means complete or final.

- Acknowledge that intersectional discrimination, marginalization, and oppression is a structural and institutional problem and is not only reflected on an individual level.

- Become aware of your privileges, reflect and criticize yourself. Acknowledge that this is uncomfortable and inconvenient and that this is exactly what is good and important.

- Inform yourself on your own, read, visit events, etc. Marginalized people do not owe you anything.

- Listen to marginalized people who experience and report discrimination and do not negate their lived experiences, but consider them as valuable and include them as important knowledge.

- Acknowledge that your own experiences, knowledge, etc. are situated, partial, and biased and do not draw conclusions about others from your own position, situation, and perspective.

- Practice recognizing structural oppression and using an »intersectional lens« to observe things and situations in everyday, private, and professional life. Who is the norm and who does it exclude?

- Ask yourself: How am I involved in maintaining and reinforcing discriminatory structures in private and professional contexts?

- Take responsibility – in private and professional life! Who do I promote, who do I quote, who do I retweet, who do I involve, who do I hire, ...?

- Talk to others about intersectionality, discrimination, and privilege – share it, name it, discuss it.

Further sources for you

The following sources are a collection of literature, people, etc. that have helped us authors (better) understand intersectionality, discrimination, and privilege. This list is by no means complete or final.

Books

- Die Kategorie Behinderung in der Intersektionalitätsforschung: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Befunde

- Die letzten Tage des Patriarchats

- Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum

- exit RACISM: rassismuskritisch denken lernen

- Feminist Disability Studies

- Fokus Intersektionalität: Bewegungen und Verortungen eines vielschichtigen Konzeptes

- Hallo, hört mich jemand?

- Intersektionalität: Geschichte, Theorie und Praxis

- Islamische Feminismen

- Lebensweltgestaltung junger Frauen mit türkischem Migrationshintergrund in der dritten Generation

- Rückkehr nach Reims

- Schwarzer Feminismus: Grundlagentexte

- Theorien der Intersektionalität zur Einführung

- (Un-)Sichtbare Erfolge: Bildungswege von Romnja und Sintize in Deutschland

- Untenrum frei

- Was weiße Menschen nicht über Rassismus hören wollen aber wissen sollten

- Yalla, Feminismus!

- Zeige deine Klasse: Die Geschichte meiner sozialen Herkunft

Article

- CIJ Factsheet: Intersectionality at a Glance in Europe

- Forgotten women: The impact of Islamophobia on Muslim women

- Gesundheitsversorgung für alle. Ohne Diskriminierung

- Intersektionalität in Deutschland. Chancen, Lücken und Herausforderungen

- Intersectional discrimination in Europe: relevance, challenges and ways forward

- „Reach Everyone on the Planet …“ – Kimberlé Crenshaw und die Intersektionalität

Websites, talks, social media, podcasts

- Center for Intersectional Justice

- Missy Magazine

- Portal Intersektionalität

- TED Talk: How to recognize your white privilege – and use it to fight inequality

- TED Talk Confessions of a bad feminist

- TED Talk Effective Allyship: A Transgender Take on Intersectionality

- TED Talk: Rethinking Privilege

- TED Talk: The urgency of intersectionality

- @alicehasters

- @EmiliaZenzile

- @LadyBitchRay1

- @marga_owski

- @modekoerper

- @sandylocks

- @sibelschick

- @teresabuecker

- @tupoka.o

- Lila Podcast

- Podcast Feuer & Brot

Project information

This project attempts to make intersectionality more accessible, to communicate its central concern and to provide an introduction. Within the context of this project, it is not possible to illustrate intersectionality in its detailed methods, theoretical approaches, levels of analysis, etc. Also, the examples given are only a small sample of the numerous, intersectional forms and experiences of discrimination.

This project is shaped by the subjective and partial perspectives of the project team. In the »Insights into the project« part, we make certain visualization decisions transparent and people involved visible. We disclose the project process, communicate the perspectives and positions of the authors and critically reflect on the project outcomes.

References

- Retrieved from https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/agg/BJNR189710006.html (09.02.21)

- Diskriminierung in Deutschland. Dritter Gemeinsamer Bericht der Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes und der in ihrem Zuständigkeitsbereich betroffenen Beauftragten der Bundesregierung und des Deutschen Bundestages. Retrieved from https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/publikationen/BT_Bericht/gemeinsamer_bericht_dritter_2017.html?nn=6569158 (09.02.21)

- Die UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention. Übereinkommen über die Rechte von Menschen mit Behinderungen. Retrieved from https://www.behindertenbeauftragte.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/UN_Konvention_deutsch.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (09.02.21)

- Zweiter Teilhabebericht der Bundesregierung über die Lebenslagen von Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen. Teilhabe – Beeinträchtigung – Behinderung. Retrieved from https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/976072/480512/6b249c2a22eb36f7a1ffb1f2029543b9/2017-01-18-teilhabebericht-2016-data.pdf?download=1 (09.02.21)

- Lebenssituation und Belastungen von Frauen mit Beeinträchtigungen und Behinderungen in Deutschland. Kurzfassung. Retrieved from https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/service/publikationen/lebenssituation-und-belastungen-von-frauen-mit-beeintraechtigungen-und-behinderungen-in-deutschland/80576?view=DEFAULT (09.02.21)

- Intersektionalität in Deutschland. Chancen, Lücken und Herausforderungen. Retrieved from https://www.dezim-institut.de/fileadmin/PDF-Download/CIJ_Broschuere_190917_web.pdf (09.02.21)

- CIJ Factsheet: Intersectionality at a Glance in Europe. Retrieved from https://www.intersectionaljustice.org/publication/2020-04-07-center-for-intersectional-justice-factsheet-intersectionality-at-a-glance-in-europe (09.02.21)

- Intersectional discrimination in Europe: relevance, challenges and ways forward. Retrieved from https://www.intersectionaljustice.org/publication/2020-09-14-intersectional-discrimination-in-europe-relevance-challenges-and-ways-forward (09.02.21)

- Theorizing Feminisms. A Reader (p. 412–418). New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (8). Retrieved from http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8 (09.02.21)

- Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

- Feminist Data Visualization. Proceedings from the Workshop on Visualization for the Digital Humanities at IEEE VIS Conference 2016.

- Data feminism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Equality data collection: Facts and Principles. Retrieved from https://www.enar-eu.org/Equality-data-collection-151 (09.02.21)

- Forgotten women: The impact of Islamophobia on Muslim women. Retrieved from https://www.enar-eu.org/Forgotten-Women-the-impact-of-Islamophobia-on-Muslim-women (09.02.21)

- Intersectional discrimination in Europe: relevance, challenges and ways forward. Retrieved from https://www.enar-eu.org/intersectionalityreport (09.02.21)

- „Reach Everyone on the Planet …“ – Kimberlé Crenshaw und die Intersektionalität. Retrieved from https://www.gwi-boell.de/de/2019/04/28/reach-everyone-planet-kimberle-crenshaw-und-die-intersektionalitaet (09.02.21)

- The work that visualisation conventions do. Information, Communication & Society, 19(6), 715–735. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1153126 (09.02.21)

- Justitias Dresscode: Wie das BVerfG Neutralität mit „Normalität“ verwechselt. Verfassungsblog. Retrieved from https://verfassungsblog.de/justitias-dresscode-wie-das-bverfg-neutralitaet-mit-normalitaet-verwechselt/ (09.02.21)

- Theorien der Intersektionalität zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius Verlag.

- Studie zur aktuellen Bildungssituation deutscher Sinti und Roma. Dokumentation und Forschungsbericht. Marburg: I-Verb.de. Retrieved from https://mediendienst-integration.de/fileadmin/Dateien/2011_Strauss_Studie_Sinti_Bildung.pdf (09.02.21)

- Für dumm erklärt - Nenads zweite Chance [Dokumentation]. WDR Doku. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miMenY9TdaI (09.02.21)

- Tans* Inter* Queer ABC. Retrieved from http://www.transinterqueer.org/download/Publikationen/TrIQ-ABC_web(2).pdf (09.02.21)

- Intersektionalität – eine Einführung. Retrieved from http://portal-intersektionalitaet.de/theoriebildung/ueberblickstexte/walgenbach-einfuehrung/ (09.02.21)

- Discrimination against Female Migrants Wearing Headscarves. In: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) (Ed.): Discussion Paper Series. Retrieved from https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/10217/discrimination-against-female-migrants-wearing-headscarves (09.02.21)

Please send us an email in case of content-related comments .

Project team

Hannah Schwan (Concept, design, text)

Jonas Arndt (Development)

Sandra Cartes (Content consulting)

Marian Dörk (Scientific supervision)